Home » Laws & Taxes » Naya Pakistan Housing Plan: A Brief Economic Analysis

Five million houses in five years—that is the dream plan painted by Prime Minister Imran Khan soon after he entered office. The plan is targeted at the lower income groups of the population, earning between Rs10,000 and 25,000 a month, and is direly needed given the startling housing statistics. The existing housing shortage is around 10-12 million houses, of which nearly half is urban, while more than 60 percent demand comes from the low-income segment. However, the current housing stock is merely 4.9 million houses, due to which critics cast doubt on the incumbent government’s ability to double the stock in just five years.

Let’s have a quick overview of the plan. The government will be the facilitator, and the regulator, and the plan will be executed with the heavy involvement of the private sector to drive and mobilize the program. As expected, the private sector has shown great interest in the project. As many as 41 private sector developers and builders with existing land banks to their name have already dropped their hats in the ring, while many others are standing in the queue. Several foreign investors, including Middle Eastern and Chinese, have expressed their interest in the project.

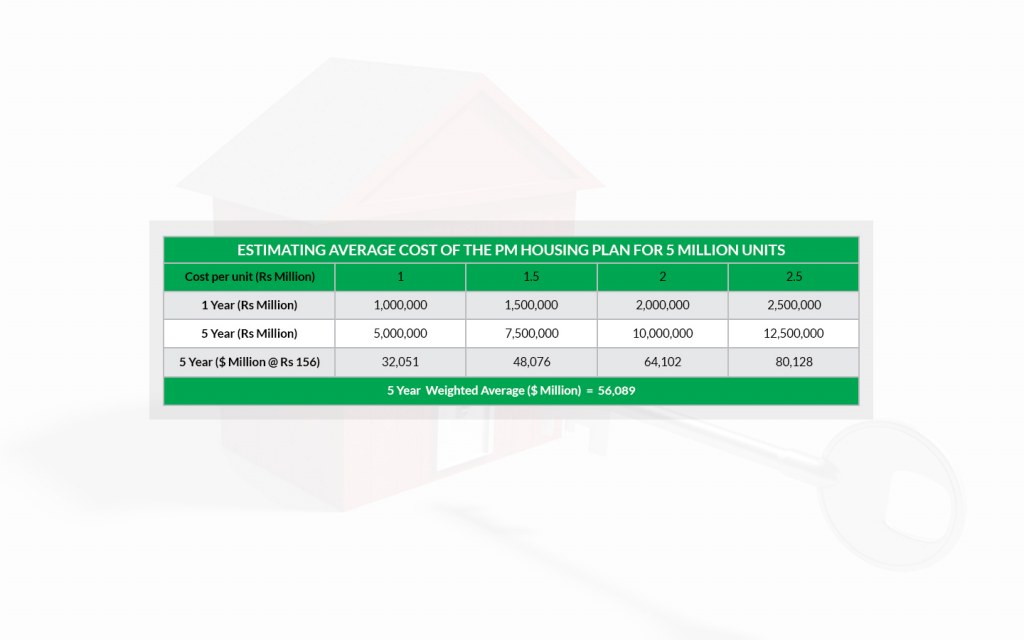

There is some contention on the total investment required. Some media estimates suggest that the five-year project needs an investment of around $180 billion. According to some critics however, generation of such a huge investment is impossible given that the amount is around 60 percent of the country’s current GDP. But the government is not as worried since the project is meant to be market driven.

However, this estimate itself seems exaggerated in the first place. If the average cost of a low-income house is less than Rs2.5 million, (which according to the SBP should be the maximum price of a low-cost home), that alone should translate into a total cost of $80 billion. Representatives of Association of Builders and Developers (ABAD) believe the correct figure is between $40-$50 billion for the entirety of the project since the cost per unit will be lower than Rs2.5 million and significantly lower in the case of rural housing.

The banking sector will be providing the mortgage for the financing, and commercial banks can raise the money required by floating bonds from investors. However, the interest rate of 13-14 percent is neither affordable for the low-income segment, nor can the difference be footed by the government.

The State Bank of Pakistan (SBP), in its low-income housing finance policy published in Nov-18, proposed that the central bank will provide refinancing facility of up to Rs1 million (or 50% of the total loan amount) to commercial banks, and at 5 percent to Development Finance Institutions (DFIs), while the remainder of the loan can be either fixed at 12 percent, or at Karachi Inter Bank Offers Rate (KIBOR) + 4 percent by the banks and DFIs. This, according to the SBP, will be provided to both individual house borrowers and housing builders/developers for low-cost housing. The average interest rate then becomes 7-8 percent.

Surprisingly, the policy was retracted in Mar-19, and replaced by a much-condensed version of its earlier edition, proposing a single financing facility for special segments including: widows, children of shaheed, transgenders, special persons, and people in areas severely affected by war against terrorism, setting the interest rate at 5 percent for them. According to the policy, SBP will finance up to 100,000 borrowers under this financing facility for special segments.

If the designed model has even lower per unit cost, owing to innovative low-cost building solutions and longer periods for mortgages, the affordability issue can be addressed. Reports suggest that applicants will pay 20 percent in down payments, which would result in even lower monthly mortgage payments.

The legislative work required specially in the form of non-judicial foreclosure framework is underway, which would empower banks to exercise their right to collateral in the case of defaults, which in turn will reduce banks’ reluctance to dole out housing loans. The National Assembly very recently passed two ordinances in this regard, the Naya Pakistan Housing Authority Ordinance 2019, and the Recovery of Mortgage Blocked Security Ordinance 2019.

The government is taking the regulatory side of the equation into account as well. A land bank registry will be created to determine the land available with federal and provincial governments, land owning agencies and the private sector. The Naya Pakistan Housing Authority on the other hand, will introduce a one-window facility which will regulate and facilitate the project.

The success of this mammoth project will require well-crafted long-term planning, and a solid financing model. Additionally, existing inefficiencies in the property and housing market will need to be tackled. This will keep the affordable housing stock growing even in the long run. Such improvements include, for example, introducing land reforms, zoning and land use laws, curtailing speculative interest in the market, documenting the real estate sector and finally establishing a real estate regulatory authority that will oversee it all. Easy to say, a lot harder to implement.

To read more on latest property related research, you can check out our piece on housing shortage in Pakistan.