Home » Laws & Taxes » Mortgage Lending in Pakistan: Stagnant Growth but Massive Potential

Housing shortage in Pakistan—which by some estimates trails between 10-12 million—faces both demand and supply impediments. One of the leading reasons is the unavailability of housing finance in the country.

In Jul-18, when the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) came out with a draft policy for low-income housing finance, there were 62,000 mortgage holders in Pakistan. Nearly a year later in Jul-19, this number has come down to 60,000 and further down to some 59,000 mortgage holders in Sep-19, as per data reported by the SBP.

It is likely that the current borrowers are being carried forward from 2007-08 when housing finance reached its peak. In fact, even if new borrowers are entering housing finance market, they are in very small ratios.

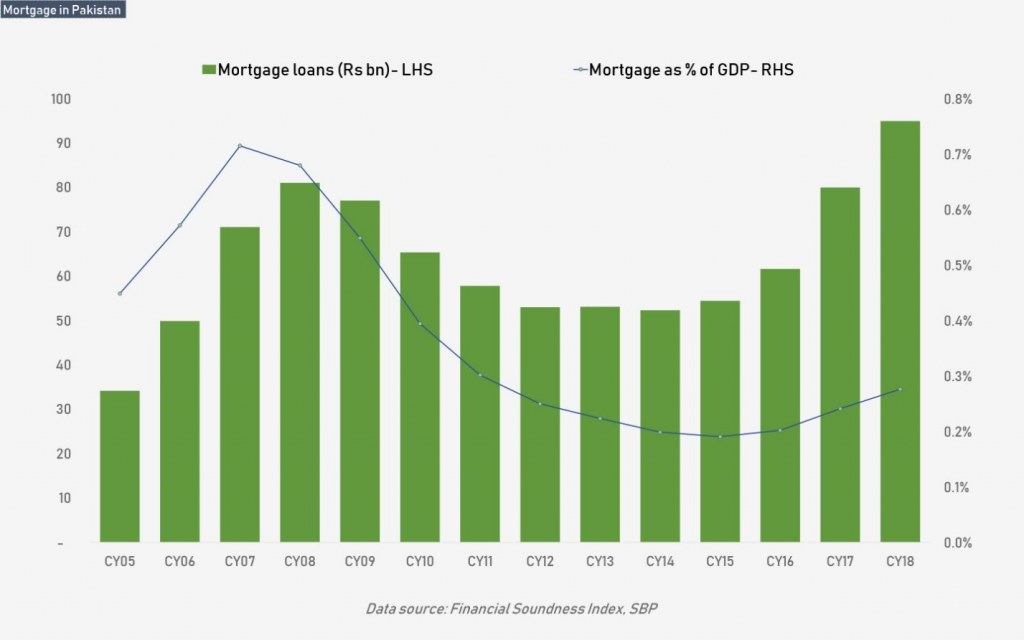

As a share of GDP, mortgage coverage crossed 0.5 percent only once in the past decade during the 2006-07 period after tumbling down once again. In CY18, it improved to a little by over 0.2 percent of the GDP, but this is only incremental from the previous years.

In comparison, India has seen its mortgage financing grow to 10 percent of GDP in 2018, from 4 percent in 2010 and 2.5 percent in 2001. Pakistan’s dismal performance in this sector can be gauged from the graph below.

A number of regulatory issues have hindered banks from expanding their housing finance base. A major difficulty remains unclear titling of land which is kept as collateral by banks. This is especially true for peri-urban, rural and urban outskirts.

There is also no centralized registry that records all the rights pertaining to land records across the country which adds ambiguity to titles. Provincial governments began the process of registration but it is neither uniform, nor complete. This is why, most properties do not qualify as security because banks can only furnish a loan if the titles of the immovable property are indisputable—evidence of which should come directly from the government.

The other issue is non-implementation of foreclosure laws. Current laws do not allow banks to exercise their right to foreclose on the properties which have gone into default. Most such cases get stuck in courts for years before they get resolved, if they ever do. In the past, lack of foreclosure laws led to many willful defaults by consumers, which made banks further averse to housing finance loans.

Judicial intervention is in disarray as well. The banking courts do not have the capacity to deal with all the cases and are currently grappling with a mounting backlog. A policy document of the SBP further broke this down: “When it comes to judicial proceedings, an important dimension is the availability of banking courts: only 11 cities in the country have banking courts. This results in inordinate delays in disposal of cases”.

A measure of ineffective contract enforcement can be gauged from the latest Doing Business indices that estimate that the trial and judgment in resolving a case takes 700 days on average in Karachi, while the enforcement of judgment takes another 300; costing 18 percent of the claim value. There is also evidence to support that court decision have been in favor of the borrower in most cases rather than the lender.

Aside from the aforementioned hurdles, two more obstacles remain: affordability and asset liability mismatch. In the latter case, because bank deposits are short term while housing is a long term asset, there is a mismatch.

To bridge this gap, the Pakistan Mortgage Refinance Company (PMRC) was formed to provide long term funding at fixed rates to banks, hedge interest rate risk and bridge banks maturity profile mismatch. Currently, the PMRC is getting a credit line from the World Bank to provide long-term loans to the financial sector which can in turn offer longer tenured loans to their customers.

The question of affordability is more complicated. Real estate in Pakistan is expensive, and due to the speculative nature of property prices, cash-based purchases are not an option for the lower-mid to low income segments.

Meanwhile, at prevailing interest rates, mortgage is simply not within the reach of the average home buyer. Since housing shortage is concentrated in the low-income segment, it is crucial to make mortgage affordable for that segment, if it has any chances of being addressed. However, as we have earlier explored, affordability of housing finance in Pakistan is still a far-off dream.

This is especially troubling given the current government’s push towards building 5 million homes for first-time home buyers, since existing interventions cannot make housing affordable for low-income and mid-to-low income households.

It is clear that the mortgage access and availability will have to be viewed from the lens of both demand and supply side dynamics. While some efforts have been made, the government has a lot to tackle— not only from the regulatory and legislative perspective, but also from the aspect of affordability which will continue to keep many deserving households outside the fringes of housing finance.

One could argue that everything cannot be addressed at the same time, in which case the priority of this government should be to build a strong regulatory framework with legal controls which would make housing finance more efficient, more transparent and thereby less risky for lenders.